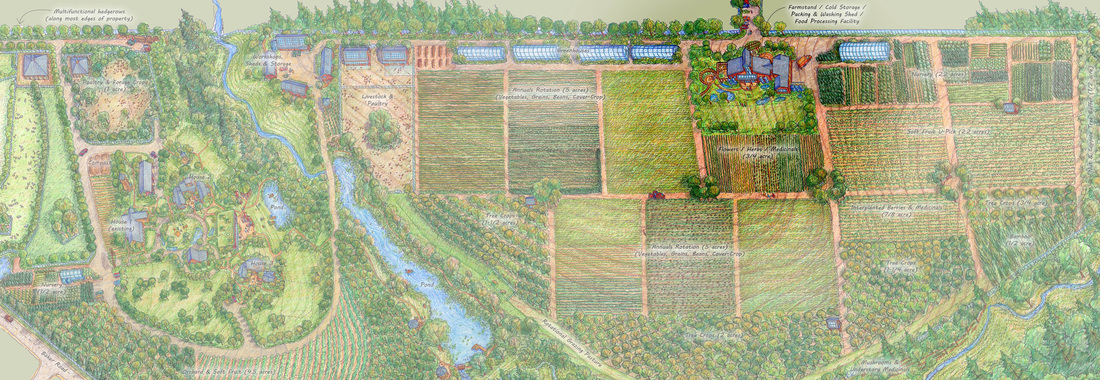

This amazing structure is one of many aspects to Our Table Cooperative Farm's property and vision...

The 58-acre regenerative farm initiative has been designed using permaculture design strategies, including perennial crops based on “food forest” design concepts, optimum crop rotations, and cooperative ownership and management. As a localization initiative, this project presents an exciting new dimension in the development of our regional food security infrastructure. The grocery offers a curated selection of foods and products, including dairy, produce, meat, health and wellness, dry goods, and prepared meals. A bulk section and a beer, wine, and growler station round out the offerings. The grocery is 85% Oregon sourced and 90% Organic with both vegan and gluten-free selections.

Integration of salvaged heavy timber from site-deconstructed barn became a focus of the building form and detail design. Scissor trusses and an exposed structure help define and give scale to an elegant central atrium. Operable clerestory windows facilitate passive cooling strategies while also creating dramatic shadows in evening sunlight and after dark. The retail grocery space comfortably accommodates shoppers, while the generous central atrium helps the building to feel even more spacious and airy.

Many of the other metal-clad service buildings throughout the property follow a simple red and white color scheme. As a special focal point, the farmstand receives a horizontal belly band to make it really stand out and drop to a human scale, accented in a complimentary plum color. Salvaged lumber from the site is incorporated both on the inside and out, contributing to an overall cozy and cohesive feel to the entire project.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed