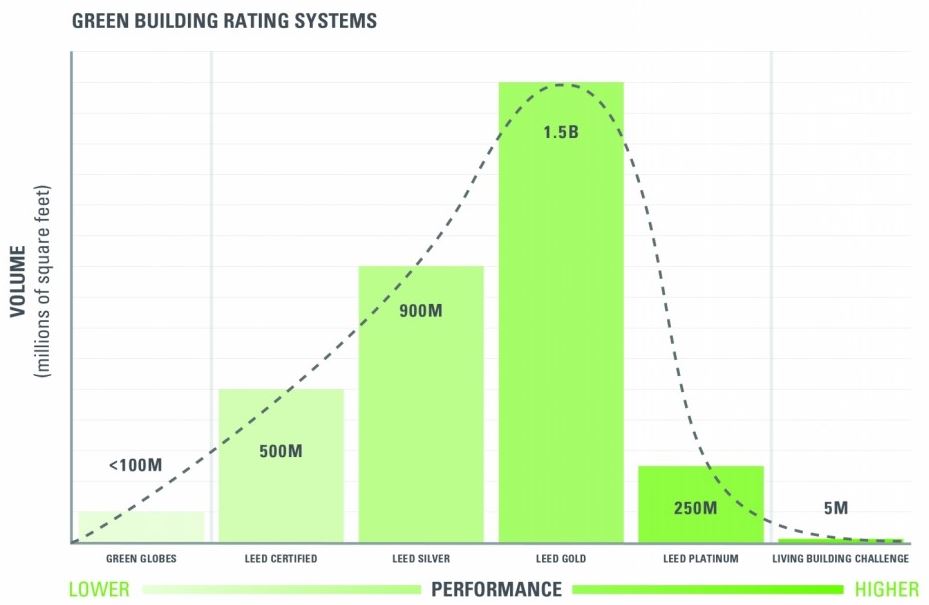

Little wonder, since the word can mean so many different things to different people. Before the U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC) launched the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) rating system in 2000, there was little consensus in this country about what constitutes a “green building.” A decade and a half later, some three billion square feet of construction have been certified under the system, and, according to estimates, LEED has cut annual carbon emissions by nearly ten million tons.

Still, some feel LEED doesn’t go far enough, a conviction that led to the 2006 formation of the Living Building Challenge (LBC), which many hold up as architecture’s most ambitious sustainability standard. If LEED serves the middle of the green bell curve, LBC targets the leading edge, an admittedly small segment of the market. What about the lagging end—the least common denominator of green construction? Even the most generous estimates suggest that only half of all new construction is being certified as “green,” and LEED’s entire volume to date represents only about one percent of the total building stock (275 billion square feet in 2010). To speed up the pace and expand the volume of certification, the construction industry urgently needs a quick, easy, affordable way to go green.

Enter Jerry Yudelson. At the beginning of the year, Yudelson, widely known as an authority on sustainable design, was named president of the Green Building Initiative (GBI). The organization runs Green Globes, an alternative to LEED that came to the U.S. in 2004-2005. In January, he announced that the goal was to address the underserved largest portions of the market with a system that is “better, faster, cheaper” than LEED.

Founded by Ward Hubbell, a former PR executive in the timber industry, Green Globes reportedly was set up as a shelter for wood products that don’t readily comply to LEED, which the American Forest and Paper Association has said “disadvantages our companies,” while “Green Globes is much more wood-friendly.” In recent years, the chemical and plastics industries have jumped on the bandwagon, because the latest versions of LEED discourage the use of certain “chemicals of concern,” specifically those found in products such as polyvinyl chloride (PVC)—the so-called “poison plastic” that the EPA, NIH, Department of Health and Human Services, and the World Health Organization all suggest can cause significant health problems. Greenpeace calls PVC “one of the most toxic substances saturating our planet and its inhabitants,” and it has been banned by various organizations, such as Kaiser Permanente.

While the LBC does prohibit PVC, LEED in fact does not; a single optional credit rewards disclosure of chemical ingredients, and specifiers are left to draw their own conclusions. Nevertheless, vinyl lobbyists take a classic slippery-slope position by treating even modest measures as threats.

Reportedly, over two thirds of GBI’s members and nearly half its board represent the timber, chemicals, and plastics industries—industries seemingly spooked by more rigorous standards for human and ecological health. Evidence shows that they’re not just backing Green Globes—they’re actively trying to undermine LEED, and there’s a lot of dirty money at play. From 2007 to 2013, the annual lobbying budget of the American Chemistry Council (ACC), a GBI member, grew by more than five times, and during that period this single organization invested a total of $62 million in influence-peddling.

It’s working: In 2012, a group of Congressmen, many of whom have received significant political contributions from the chemical industry and the ACC itself, urged the General Services Administration (GSA), which manages much of the federal government’s construction, to drop LEED: “We are deeply concerned that the LEED rating system is becoming a tool to punish chemical companies and plastics makers and spread misinformation.” They claimed that vinyl products “are universally considered the most durable, sustainable, and energy efficient by the construction industry” and that their restriction would “severely harm manufacturing in this country.”

Arguing that LEED (or the LBC, for that matter) seeks to “punish” chemical and plastics makers by discouraging the use of potentially harmful substances is like saying that energy efficiency is intended to punish fossil-fuel companies. Nevertheless, last fall the GSA, whose annual buildings budget can be in the tens of billions, endorsed Green Globes for the first time. Additionally, over the past year or two, multiple states, including Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, and Ohio, have adopted legislation banning LEED in publicly funded buildings.

Given all of this, I was surprised this week when the USGBC and ACC announced that the two organizations would be working together “to improve LEED”: “USGBC and ACC share the goal of advancing sustainability in the built environment,” USGBC President and CEO Rick Fedrizzi wrote in a press release, adding that both entities “will work together to take advantage of our collective strength and experience.” Time will tell exactly what this means. Will the chemical industry embrace smarter solutions? Will LEED become more accommodating to status-quo chemistry? Or is this just the USGBC’s politically astute way to give the ACC a more formal avenue for discussion, in order to defuse anti-LEED lobbying?

In the meantime, Green Globes continues to try to get more market share, and the GBI remains dominated by the timber and chemical industries. So when Yudelson took over in January, I got excited, since I have known and admired him for years. Could he turn Green Globes around?

Immediately upon joining, he announced that he views GBI’s role as that of a “‘friendly competitor,’ rather than a nemesis” to the USGBC: “I don’t really see us getting engaged in anti-LEED activity as an organization.” Privately, he maintains the same position: “GBI is not a lobbying organization,” he assured a group of my peers and me in July. “We do not coordinate with any groups that might lobby for or against other green building rating systems, nor do we participate in such political discussions.”

Yet, in late January—two weeks after Yudelson’s initial claim that his organization planned to stay above the fray—GBI board member Allen Blakey, a vice president with the Vinyl Institute, testified before the Ohio state legislature in support of a proposed ban on LEED, calling its new material standards a “discriminatory and disparaging treatment of vinyl.” This isn’t “friendly” competition. GBI is a charitable organization whose tax-exempt status is contingent on protecting the public good, not private interests, and at least one of its directors appears to be toeing a very fine line between the two.

Since taking his new role, Yudelson’s positions seem to have changed in favor of private interests, as well. Last year, before joining GBI, he told a reporter, “We know that a lot of these substances [in materials] have long-term effects [on health].” Since taking his new post, however, he declares, “I haven’t seen persuasive data on the health outcomes of common building materials.” This April, Yudelson called vinyl “benign in use,” possibly contradicting a 2009 report he co-authored (“Inside Going Green”): “PVC is inexpensive and routinely used, but it presents serious fire smoke hazards. Even before it ignites, it releases deadly gases such as hydrogen chloride….Dioxin, the world’s most potent carcinogen, is released when PVC burns.” Since most buildings don’t catch fire, is the phrase “benign in use” Yudelson’s way of sidestepping the “serious hazards” he once attributed to vinyl? Regardless, the EPA, however, classifies vinyl chloride as a carcinogen and maintains that exposure can occur in everyday uses.

Even if the facts about PVC and other materials weren’t “persuasive,” as Yudelson claimed this year, scientists and sustainability leaders long have subscribed to the precautionary principle, which holds that “when an activity raises threats of harm to human health or the environment, precautionary measures should be taken even if some cause and effect relationships are not fully established scientifically.” Yudelson himself advocated for this approach in an interview last year: “[W]e may be creating long-term unhealthy environments even while we’re doing all of these green upgrades. The overarching principle is that we ought to err on the side of caution.”

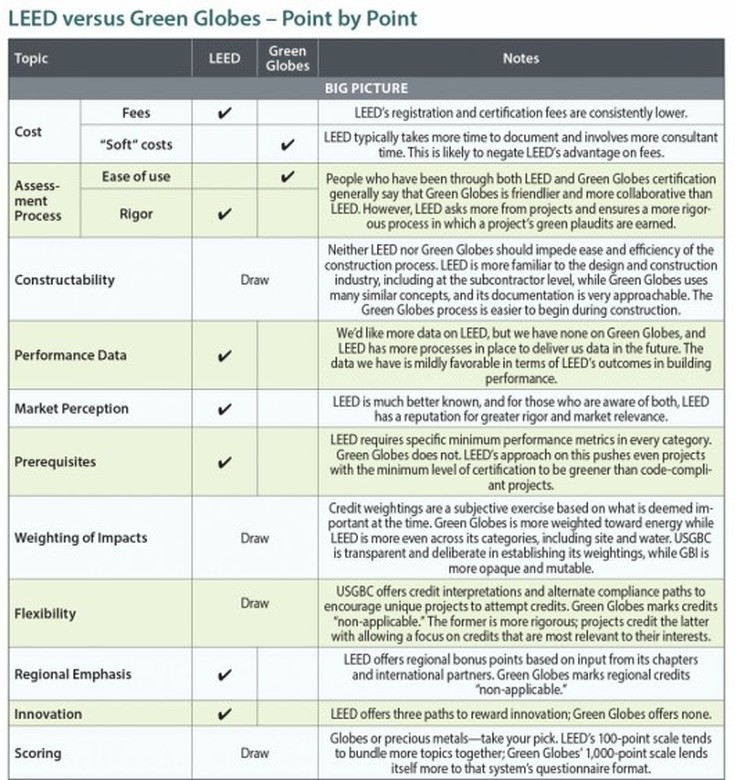

Yudelson contends that Green Globes is “basically identical” to LEED. Last year, the Portland Tribune considered the merits of the two systems and concluded, “LEED is a more rigorous, broad-based, credible system that delivers more environmental benefits.” This June, the independent consultancy and publisher BuildingGreen released a 90-page “definitive analysis” and found that, in some cases—but only some—Green Globes can be “faster and cheaper” than LEED, as Yudelson insists. But “better”? No. The report specifically calls attention to Green Globes’ weaknesses around the health impact of materials.

In late May, a handful of green building experts and I met with Yudelson to discuss his plans for GBI. We specifically asked him about the board’s composition, anti-LEED lobbying, the health impact of materials, and other important subjects. While the conversation was pleasant, on these topics I found him to be evasive, but he said he would get back to us “within a couple of months.” On June 9, we followed up with a letter, signed by the sustainability leaders of thirty prominent architecture firms, imploring Yudelson to discourage lobbying and campaigning against LEED by stating publicly that GBI does not condone such activities: “We are deeply concerned that a continued campaign against LEED hurts the green building industry as a whole,” we wrote. “The real campaign should be one where all viable green building systems fight shoulder to shoulder to beat back the negative impacts of the built environment.”

Later that month, on June 25, Yudelson sent an email blast to hundreds of industry insiders, criticizing the BuildingGreen report: “Grow[ing] the overall green building market…should be our mutual goal, not engaging in attacks on the merits of one rating tool vs. another.” On July 12, Yudelson finally replied to our letter from June 9: “I don’t think it’s my role or GBI’s to rise to the defense of a competitive product.” He also asked why we haven’t discouraged “relentless and unfair” attacks on GBI by other organizations (not knowing that some of us actually have spoken to others about raising the level of debate).

In response to this week’s USGBC/ACC press release, Yudelson emailed the group that met in May: “I hope [this will] cause your group to reassess where GBI is coming from in our preference that materials credits (and choices) be based on sound science and proven risk-assessment methods.” Again, this appears to be quite a different attitude from his past recommendations to embrace the precautionary principle.

Six years ago, in The Green Building Revolution (2008), Yudelson defined a “green building” as “a high-performance property that considers and reduces its impact on the environment and human health” [emphasis added]. The building industry urgently needs new solutions that drive wider adoption of green practices, but no sustainability standard can be considered credible today if it does not reflect the latest thinking about the health impact of materials.

Lance Hosey, FAIA, LEED AP, is Chief Sustainability Officer with the global design leader RTKL. His latest book, The Shape of Green: Aesthetics, Ecology, and Design (2012), has been Amazon’s #1 bestseller for sustainable design. Follow him on Twitter: @lancehosey

Citation: Hosey, Lance. "The Green Building Wars" 17 Sep 2014. ArchDaily. Accessed 22 Oct 2014. <http://www.archdaily.com/?p=549176>

RSS Feed

RSS Feed